The Unquestioned Transition

The Unquestioned Transition

On June 17th, we went to the National Assembly to hear from Tony and learn about what their program all does and their viewpoint on Catalonian's. This presenter was very interesting because he had personal stories from not only himself but also his family. I really enjoyed this visit because it was more of a direct conversation about Catalonians with no information "hidden".POL 150 Connection

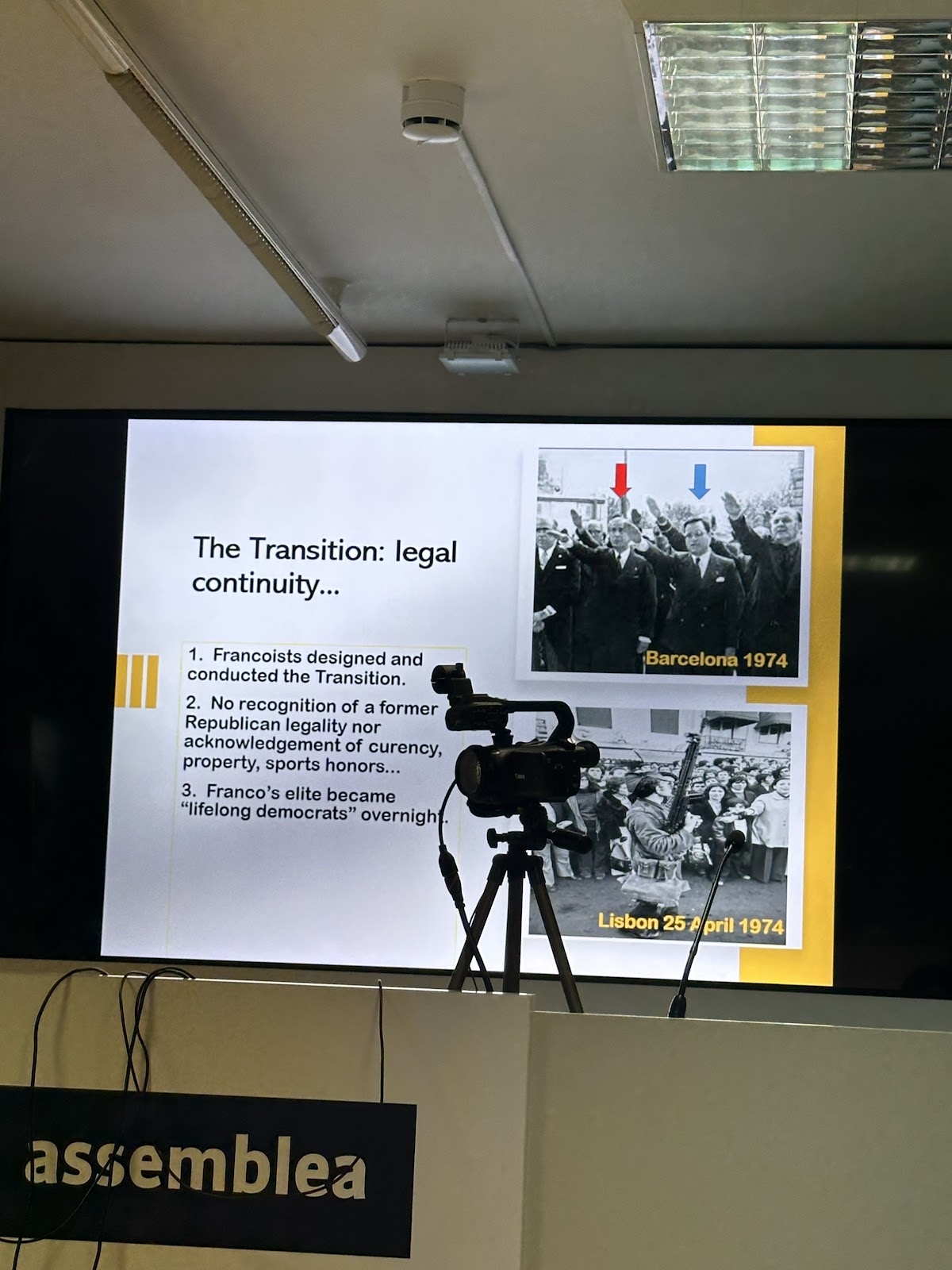

Spain’s transition to democracy (known as La Transición, 1975–1982) is often described as “unquestioned” in the sense that it was widely accepted as necessary and was marked by a national desire to avoid another civil war. However, that very consensus also shaped how issues of equality, especially political, social, and historical, were handled, often by avoiding them. For example the pact of forgetting. The political elites agreed not to address the crimes committed during Franco's dictatorship (1939–1975) in order to maintain peace and unity. The impact on equality are the victims of the regime, such as political prisoners, the families of the disappeared, and regional minorities; who were denied truth, justice, and reparations. This undermined equal recognition under the law. Secondly, we can look at the top-down transition. The shift to democracy was negotiated between Francoist elites and moderate opposition leaders, with the monarchy playing a key role. The impact on equality are many grassroots movements (e.g., workers', women's, and regional rights movements) were sidelined in favor of a controlled, elite-led process. This limited participation and representation in shaping the new democracy.

POL 130 Connection

Spain’s “unquestioned” transition to democracy is deeply intertwined with contentious politics, not because it was filled with open conflict at the time, but because its apparent consensus suppressed contention rather than resolving it. This created long-term tensions that later erupted into political and social disputes. For example, suppression conflict through consensus. The transition emphasized elite pacts and consensus-building, aiming to avoid conflict after decades of dictatorship and civil war. The relevance to contentious politics is by avoiding confrontation over sensitive issues, like Franco’s legacy, regional autonomy, or class justice. The transition postponed rather than resolved major grievances, sowing the seeds for future contention. Secondly, you can also look at the "Pack of Forgetting" as conflict avoidance. Political forces agreed not to seek accountability for Franco-era crimes to maintain peace. The contentious impact is that this created a deferred struggle over historical memory, justice, and legitimacy, which resurfaced later through movements demanding truth and reparations (e.g., exhumation of mass graves, renaming streets). Lastly, we can look at the marginalization of grassroots movements. The transition was largely negotiated by elites like Francoist reformers and moderate opposition, rather than through mass mobilization. The result of this are social movements (workers, feminists, regional nationalists) were pushed to the margins. Their exclusion created underlying tensions that later fueled contentious mobilizations.Compare & Contrast

One connection between POL 150 and 130 is that both were constrained by elite consensus. The transition prioritized stability over transformation, which meant both contentious demands (like regional autonomy or justice for Franco-era crimes) and calls for equality (gender, economic, political) were sidelined. This created unresolved tensions for groups seeking justice or equality had to push outside the formal system, i.e., through contentious politics, to be heard. Secondly, inequality became a driver of contention. Unaddressed inequalities like regional, historical, gender-based, fueled protest and activism. For example, the lack of recognition for Franco’s victims led to memory movements, while the marginalization of Catalan identity helped spur independence mobilizations. In this way, the absence of equality produced contentious responses. In contrast, contentious politics focuses on how people mobilize to challenge power structures and equality focuses on fair distribution of rights, resources, and recognition. Secondly, they differ during the transition. For instance, contentious politics largely discouraged or suppressed to maintain order (ETA). For equality, it is more promised like in the constitution but unevenly implemented. In summary, contentious politics and equality are intertwined in Spain’s transition, because the failure to achieve deep equality (justice, recognition, rights) often led to contentious mobilizations. Both were limited by the desire for peace and stability during the transition. But while equality was written into Spain’s new democratic framework, contentious politics was often repressed or discouraged, only to resurface when those promises of equality were not met.New Knowledge

After engaging with Spanish culture and history, particularly through learning about the transition to democracy, I now understand how deeply the past still shapes present-day Spain. Before, I saw Spain mostly through its vibrant traditions, food, and festivals. But now, I realize that beneath those visible aspects lies a complex legacy of dictatorship, civil war, and silent compromises.

I didn’t know how deliberately Spain avoided confronting its past during the transition, and how that decision, often praised as peaceful, left many voices unheard like victims of Franco’s regime, regional nationalists, and women demanding equality.I also gained a new appreciation for the diversity of Spain’s people. The strong regional identities in places like Catalonia and the Basque Country aren’t just cultural differences but they reflect deep historical struggles for autonomy and respect that continue today. I now see that Spain isn’t one unified identity, but a mosaic of languages, histories, and political perspectives.

Finally, I came to understand that contentious politics, like protests, independence movements, and memory activism, are not signs of instability but of a democracy still wrestling with its past. They are evidence that many Spaniards are actively engaging with questions of equality, memory, and justice that were once silenced.

Some benefits to this experience would include firsthand insight into Catalan Nationalism and self-determination, a closer look at grassroots democracy and contentious politics, and understanding ongoing tensions in Spain's democracy.

Comments

Post a Comment